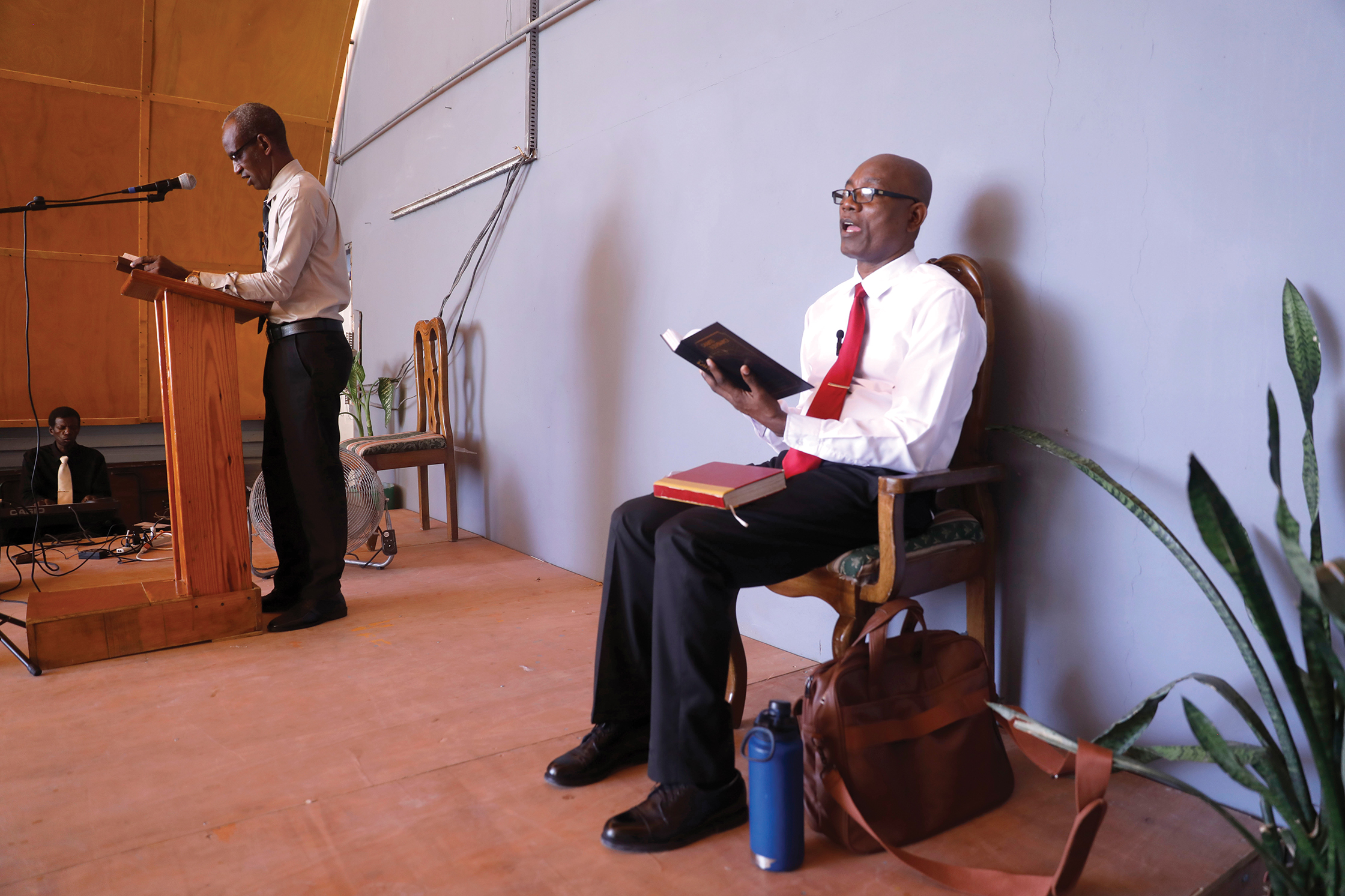

For the last few years, Haitian pastor Octavius Delfils has been preaching through the Gospel of John.

Throughout that time, Haiti has endured a presidential assassination, a 7.2-magnitude earthquake, and a spiral of gang-fueled violence that has plunged the Caribbean nation into an even greater crisis than did the devastating 2010 earthquake that killed an estimated 200,000 people.

Another alarming trend: Nearly half the Haitian population is facing acute hunger. By the end of 2023, 97 percent of the population in some cities faced severe hunger, with most Haitians surviving on one meal a day.

Given the string of calamities, some pastors might consider turning to topical sermons: How should Christians respond to violence? To disaster? To poverty?

But Delfils feels his congregation in the country’s capital, Port-au-Prince, is better served by focusing on Jesus’ words in the fourth Gospel:

“I am the good shepherd.”

“I am the bread of life.”

“The thief comes only to steal, kill, and destroy. I came that they may have life and may have it abundantly.”

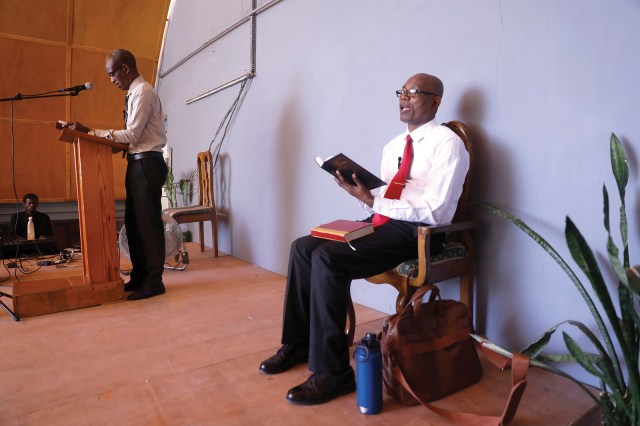

Photo by Octavio Jones / Genesis

Photo by Octavio Jones / GenesisWhat does abundant life look like in such dark days? How does a local pastor shepherd a congregation scattered across a dangerous city? How does a minister tend to bodies and souls hungry for daily bread and bread from heaven?

For Delfils, the answers are more ordinary than heroic. He preaches through the Scriptures in his local church. He feeds hungry children in his corner of the city. And as many Haitians flee the country, he stays.

Staying put is its own ministry in a nation where many aid organizations, foreign mission groups, and government entities no longer can run big programs because of perilous conditions. Daily provision now comes more modestly—often methodically, block by block, and sometimes pastor by pastor.

“I know that it’s dangerous,” Delfils says. “But I know that the Lord is there.”

Looking for danger is part of the pastor’s daily routine.

When he wakes in the morning, Delfils and his wife listen to the radio to plan their day. Is it safe to leave the house for groceries? For gas? Scanning Facebook and WhatsApp sharpens the picture, as ordinary Haitians offer intel on what parts of the city to avoid.

The situation changes daily. Gangs may block a neighborhood street for a few hours or a few days. Other parts of Port-au-Prince remain no-go areas, too unsafe to visit. Some areas are so treacherous that residents have abandoned their homes.

That includes Delfils.

The pastor once was building a home across town, after losing his previous house in the 2010 earthquake that leveled much of the capital. But now it’s too dangerous to visit his new home. Thieves took the water pump from the well outside. Delfils heard they stole building materials from the yard. A relative recently finished a house in the same neighborhood, only to have it looted.

“They came inside and took everything, all the furniture,” the pastor says. “Everything is gone.”

For now, Delfils leases a house near the congregation he serves that’s part of the Reformed Presbyterian Church in Haiti.

Photo by Octavio Jones / Genesis

Photo by Octavio Jones / GenesisThese days, sections of the city that once bustled with motorcycles and vendors and women carrying babies on their backs are now hushed. Running essential errands means heading out and coming back as quickly as possible. Often, Delfils says, “it’s like we are prisoners in our homes.”

As hard as other hard times have been in Haiti, Delfils, 55, says this is the worst he’s seen. Since Jovenel Moïse, Haiti’s last democratically elected president, was assassinated in 2021, entrenched gangs have filled a power vacuum and now control most of Port-au-Prince.

They also control major roads leading into the city—severing vital routes that businesses, hospitals, and aid groups depend on for transporting goods. Attempts at crossing gang-controlled areas risk extortion, robbery, or kidnapping.

Even in churches, long seen as sanctuaries, many leaders and worshipers no longer feel safe. Some church buildings have been attacked and looted. In one high-profile kidnapping, gunmen killed a deacon and snatched his wife outside a Baptist church on a Sunday morning. In another incident, assailants kidnapped members of a worship team during a live stream service.

The world was shocked when, in October 2021, the 400 Mawozo gang abducted a missionary team of 16 US and Canadian citizens outside Port-au-Prince. The gang demanded $1 million for each member of the group, most of whom remained in captivity for 61 days before escaping.

But Haitians are by far the most common targets for kidnappers, and the ransoms demanded are usually much smaller. Kidnappers sometimes pluck children from the street and demand whatever a family can afford.

Most church gatherings have been spared, but many church members wonder: How now shall we gather?

For Delfils, the answer hasn’t been easy, but it’s been clear: We keep coming to the house of the Lord.

Preparing for Sunday mornings starts on Mondays.

As Delfils studies the Gospel of John for his sermon, he also studies any hot spots near the church to make sure worshipers can get to the building. Usually, they can. But occasionally, blocked roads make access to the area impossible and some decide to

stay home.

One woman told Delfils that two Sundays she was stopped by armed men in the street on her way to church. (They eventually let her pass.)

Another pastoral task: How to shepherd the flock during the week? Delfils describes this as one of his biggest burdens. He wants to be able to visit church members, but often it’s too unsafe or roads aren’t accessible.

Photo by Octavio Jones / Genesis

Photo by Octavio Jones / GenesisWhile phone calls and Facebook messages help, the pastor longs to be in living rooms with his church members and next to their hospital beds, helping them face the traumas of their everyday.

“We had one lady who was kidnapped at her work,” Delfils says. “She’s a nurse and she was working during the night and people came with weapons and kidnapped her.” At least three of his church members have been chased from their homes and can’t return. One family has chosen to stay in a dangerous area, and Delfils worries about them.

Some members are burdened for their pastor. When a gang briefly took over Haiti’s main fuel depot and triggered a severe gasoline shortage, friends dropped by Delfils’s home to share a few gallons with him, making sure he could drive to church on Sunday morning.

Travel may be complex, but the heart of Sunday services remains simple: The congregation sings, prays, confesses their faith, listens to the pastor’s sermon, witnesses baptisms, and takes the Lord’s Supper. Delfils says the ordinary means of grace strengthen God’s people for extraordinary times.

People sometimes question whether they should meet in person, but Delfils insists that the church remain open. “I explain that we need to continue to serve the Lord,” he says. “We can do that.” He says while online meetings are occasionally necessary, “the fellowship of the church—we cannot replace that. . . . We don’t want to miss being face-to-face.”

Another thing that can’t be replaced: the Lord’s Supper. The church has been able to buy bread and still has enough communion cups to keep serving the congregation.

Once a month, the Lord’s table stands as a reminder: Jesus is living bread, broken for sinners living in a broken world. And sometimes the Bread of Life surprises his children with joy.

In John 6, Jesus is concerned about a crowd of hungry people.

They’ve been following him in a remote place and listening to his teaching. Jesus asks one of his disciples where they can buy bread so the people can eat. Philip balks at the impossibility of the question, but Andrew points out a boy with five loaves and two fish.

Jesus feeds the 5,000.

In much of Haiti, hunger seems like an impossible problem. The UN World Food Program (WFP) reports the country has one of the world’s highest levels of food insecurity, with more than half of its population chronically food insecure and 22 percent of children chronically malnourished.

Between August 2023 and February 2024 alone, the price of food rose by 22 percent, making it even less affordable for millions of Haitians.

Delfils translates the statistics to daily life: A single meal from a street vendor can cost about a day’s wages for a typical Haitian worker. For some, wages are far lower and food far more expensive. Delfils estimates the average family subsists on one meal a day.

“I don’t know how people are living with the money they make,” he says. “It’s a miracle they are.”

Delfils hasn’t miraculously fed 5,000 people, but he has methodically fed 500. That’s the number of children who attend the school Delfils helps to run. He’s taught at the Christian school for years, and his church has long met on the grounds. But when missionaries associated with the project had to flee the country, Delfils and local workers kept the K–12 school going.

For many children, the daily meal of rice, beans, and meat is a literal lifeline. Donors outside Haiti help fund the food budget that’s almost as much as the budget for salaries. Delfils finds children and their parents aren’t just hungry for food. They’re hungry to learn and grow—to keep coming to school, despite the dangers.

When the church organized a Vacation Bible School program over the summer, 300 children showed up. In the comfort of a secure compound, “they spent the days learning from the Word, playing games,” Delfils says. “It was a lot of joy.”

It was so much joy, a couple dozen of the children kept coming back for Sunday school on Sunday mornings, joining church members already gathering to feed on fellowship and the Bread of Life Jesus revealed himself to be in the Gospel of John.

Delfils says that gives him hope at a time when many concerned friends and family members are urging him to leave Haiti. The people need a shepherd, he says. And Haiti needs the church.

“The only place where change can start is for the church to listen to the Word and live the Word, and people will see how we have hope in the midst of the catastrophe in Haiti,” he says.

“I believe only the Lord can do something for Haiti.”

Jamie Dean is a North Carolina-based journalist with two decades of experience in domestic and international reporting.