This article was originally designed as a podcast. For the best experience, listen to the audio.

“Actually, going to Iowa State was a last-minute decision,” said Haywood Stowe. “I remember that whole time of beginning the school year—there’s all these events going on, and people would say something they were going to go do, and then throw ‘Salt’ on the name of it. They’d be like, ‘Yeah, we’re going to this volleyball thing. Apparently, it’s through Salt.’ Or they’d say, ‘Oh, there’s this stuff going on at MWL fields by the residence halls, and there’s these Salt people doing it.’ And I’m like, What the heck is this?”

Haywood is a junior at Iowa State University this year.

“So I’m just hearing this Salt, and I’m thinking it’s a school thing,” he said. “So I go to them: I went to volleyball, I went to all these things. And I was like, Man, these people know how to have a good time. They know how to do fun stuff . . . You could tell there was something different about them. I didn’t put my finger on it [right away], but [eventually] I was like, You guys must be Christians. There’s something fishy here. None of y’all are saying any bad words this whole entire time. They’re a little too kind, a little too demure.”

Haywood grew up in a Christian home. He knew that Jesus had died for his sins, that the Bible is true, and that God’s plans for his life are best.

“I did understand it,” he said. “I just didn’t care.”

Until he got to college and was invited to join a small connection group associated with Salt.

“Honestly, that’s how my life changed, because I got what I’ve never had in my life, which was actual community—meeting people that were on fire for God but then really cared about you,” he said.

Haywood was hooked—and he wasn’t the only one. The Salt Company is probably the biggest campus ministry you’ve never heard of. It was started in the late 1980s by a tiny Baptist church near the University of Iowa. Nearly 40 years later, there are Salt Companies on 33 campuses in 16 states, reaching more than 12,000 college students a year.

They do a lot of things you’d expect—large praise-and-worship gatherings, smaller Bible studies, and summer mission trips. But they also do some things you wouldn’t anticipate, like being so committed to the authority of the local church that if they can’t find a suitable congregation near campus willing to partner with them, they’ll plant one. Like taking kids through a gospel class that’s essentially Reformed systematic theology. And like talking over and over about sin.

I love the local church, and I think we should talk more about sin. But that’s not why I love this story so much.

“Before college, my faith was just a little flimsy thing, and now it’s just like the air that I breathe,” said Haywood’s friend Morgan Panosh. “It’s what gets me out of bed; it’s what excites me. It’s the desire of my heart. [When] overseas this summer, I spent every day reaching as many people as I could with the gospel in a new environment. It wasn’t like, Oh, it’s Iowa State—I’ll see him again. It was like, I’m never going to see these people again. And being surrounded by spiritual corpses. So now I came back and I’m like, I just want to share the gospel.

Haywood agrees: “Yes, oh my gosh, I know exactly what you’re talking about.”

We hear a lot about Gen Z these days—they don’t go to church, they don’t trust institutions, they don’t read their Bibles, and they don’t believe in Jesus.

And that’s true—in some ways. Overall, they don’t do any of those things as much as their parents and grandparents did. And yet if you talk to campus ministry leaders, they’ll tell you Gen Z is looking for help. Their culture is asking them to form their own identity around the rapidly changing trends on social media. This is leading to all sorts of problems—anxiety, addiction, and sin. Gen Z is struggling to find out who they are, what’s real, and if there’s anything they can trust. Many of them are finding it in the gospel.

Campus ministry leaders keep telling me it looks like a revival is starting to bubble. In some places, like Salt, it’s boiling over.

Gen X

Before we talk about Gen Z, we need to talk about Gen X.

When Gen X was in college, back in 1985, Ronald Reagan was beginning his second term, Nintendo was making its American debut, and teacher Christa McAuliffe was selected to join the crew of the space shuttle Challenger. That same year, Troy Nesbitt took his first job.

“I was offered the job of freshman director of the Baptist Student Union, which at that time had about 60 students, and I would just work with freshmen,” Troy said.

The Baptist Student Union is the college ministry of the Southern Baptist Convention. It was founded in 1919 in Texas, and like the Convention, had grown like crazy. By the mid-1990s, it was larger than Campus Crusade, Navigators, and InterVarsity combined.

Troy was young—just out of college himself. He was energetic and fun—when the students managed to get 100 people to a large-group meeting, he shaved his head. And he loved the Bible.

As Troy enthusiastically helped students understand the gospel, the ministry grew more rapidly. When the lead director position came open two years later, Troy was an easy pick to fill it.

Brent Haverkamp was a junior at Iowa State that year. He and his friend Chad were looking for a solid campus ministry.

“We went and visited every Christian student group that we could find at Iowa State,” Brent said. “Third week in the semester, we went to a little group called Baptist Student Union. And it was Troy Nesbitt’s first year of leading. . . . Chad and I looked at each other and said, ‘Oh, we found it. We just found it.’ And I think it was because it was real and authentic.

“People weren’t putting on a show. They were just trying to figure out how to follow Jesus. . . . Troy is one of the most authentic people that I know. And he’s very transparent and vulnerable. And that was something I was unused to, in a more formal, a little more liturgical church setting. And so really, that was the start of a whole changed life for me.”

Brent loved the way Troy didn’t paper over the parts of Christianity that can seem boring or confusing. He loved that Troy confessed his mistakes and sin out loud. He loved that Troy didn’t always know what to do but was always eager to do something.

Brent also loved the people Troy was gathering, especially a girl named Tori.

“I came from a Methodist background, but I wasn’t really a Christian,” Tori said. “I didn’t understand the gospel. My sister had visited with a friend of hers and she said they called it Thursday Night Thing: ‘You have to go to the TNT—Thursday Night Thing—with me.’ And so she started understanding the gospel, and then she brought me in. I went to a retreat probably in the spring of that year, became a Christian, and just ate it up. It was all so different than I knew church to be.”

Kids were being saved, lives were being changed, couples like Brent and Tori were dating and getting married—Troy should have been thrilled.

But he wasn’t.

“I was just convicted biblically that I didn’t want to lead a parachurch ministry or a denominational ministry,” he said. “I wanted to lead a local church ministry.”

To me, today, the desire to bring campus ministry under the authority of a local church sounds good and right. But that wasn’t a normal desire back in the 1980s. The most well-known campus ministries—from the Navigators to Young Life to Campus Crusade for Christ—were parachurch organizations. In other words, they weren’t under the authority of a single church but worked alongside many churches. Other ministries, like the Baptist Student Union, were under the authority of a denomination but only loosely connected to local congregations.

Neither of these was a bad model. Both allowed smaller churches to combine their resources to support a larger ministry, and the parachurch model also allowed campus ministries to avoid getting stuck in denominational identities. If you went to the Baptist Student Union, you were probably Baptist. But if you went to InterVarsity, you could be from any denomination.

Troy knew about those advantages. But he also knew something else.

“In the midst of that studying the Scriptures, I saw that the local church was God’s plan A, and the reason that churches weren’t reaching college students was because college students don’t pay the bills. And you could see these historic church facilities adjacent to every campus, but students weren’t going there. And so I felt like the parachurch experience that I’m so grateful for—Bill Bright and Dawson Trotman and Stacey Woods—who knew the church was neglecting the next generation, and so they did what they did. But I just, in my conscience, wanted to have a church-based college ministry. I wanted to disciple students in the context of the local church.”

The Salt Company

In pursuing his convictions, Troy had a huge advantage: His dad was the pastor of Grand Avenue Baptist Church, which sits about a mile and a half from Iowa State in Ames. Without too much trouble, Troy moved his ministry there. He was still raising his own support, but now he was on staff at the church and under the authority of the leaders there.

With its new name—The Salt Company, after Matthew 5:13—and new church connection, the ministry grew rapidly. Within a few years, it had grown to 200 students. Another 50 students had graduated, married each other, settled down in Ames, and joined Grand Avenue.

If you’re counting, that’s about 250 church attendees younger than 30.

“And then maybe there’s 150 [people] who are maybe 40 and older,” Brent said. “And that was the divide at Grand Avenue.”

Divide is exactly the right word for it. Within a few years, this traditional Baptist church had been swamped by students.

Some church members were uncomfortable with the name Salt, wondering if the students were trying to distance themselves from the Baptist label. Some didn’t like the way the students dressed or the way they were pushing for a more contemporary worship style. Troy and his team didn’t like the way the church limited their small salaries—which they were raising themselves—to what it could afford to pay its staff.

“My dad and I were not in conflict, but I was in conflict with much of [the leadership] of the church,” he said. “I would have got fired at least three times had it not been for my dad.”

Troy’s experiment seemed to be failing miserably. The natural solution was to stop, back up, and return to the parachurch model.

“My brother and Pete, who were two guys that were on staff with me full-time, said, ‘Troy, let’s just start a church,’” Troy said.

Or you could do that. Starting a church that welcomed, focused on, and prioritized youth was an interesting idea. Troy’s a bold guy, but in this, he was hesitant.

“And I said, ‘I’ve been a maverick and a rebel, and I’m just not going to do it,’” he said. “I wanted to serve my dad. I wanted to faithfully leave the church, and I wasn’t going to do that unless we could get the blessing of the church, and there was no way we were going to get that.”

Troy and his wife broached the idea over lunch with his parents.

“God had already done a work in their hearts,” he said. “I think they were kind of ready.”

Cornerstone Church

Grand Avenue voted to plant their young people in a new church called Cornerstone. Right off the bat, there were financial troubles: Cornerstone hardly had anybody older than 30. Most members were still in college; the rest were early in their careers. There was no real money.

At the same time, there was a real financial need. You can’t fit 250 people into a living room. You can’t cheaply feed them or provide discipleship materials for them. You can’t really even have a bivocational pastor, because he wouldn’t have enough hours left in his evenings and weekends to adequately care for the people.

“[My wife] Teresa and I both gave plasma twice a week, and that was our food budget for our family,” said Jeff Dodge, who moved his family to Ames so he could take care of The Salt Company while Troy focused on Cornerstone.

“When the growth was happening so fast, anytime there was extra money in a budget that could have maybe gone to a raise or whatever, we wanted to hire more staff or we wanted to get out of this rental situation we’re in,” he said. “There’s always something, it seemed like, more worthy than [anything] personal. And I was all in—I’m not saying that begrudgingly, like somebody else did that to me. I’m saying collectively, we were all in. That went [on] for a while, I’m not gonna lie.”

It went on for a few years. The church members held garage sales, sold cinnamon rolls from folding tables outside Walmart, and bought their clothes at thrift stores. They gave each other haircuts, quit going to movies, and ate at home. They delayed buying houses or furniture, handed over their year-end bonuses, and asked Salt alumni for donations. Anything they earned or saved went to the church. Still, they were nearly always out of money because the ministry wouldn’t quit growing.

The 1990s was a heady decade for American evangelicals. While mainline church attendance was already dropping, the percentage of evangelicals was peaking. With 15,000 weekly attendees, Willow Creek Community Church near Chicago was a prototype of the new seeker-sensitive megachurch movement. In Atlanta, Andy Stanley was doing the same thing. Within five years, his North Point church plant had 5,000 members and an 83-acre campus. In California, Rick Warren’s Saddleback Church was busy building a $12 million, 3,500-seat worship center.

In Iowa, the number of Salt students tripled from 200 to 600 in the first 10 years. Cornerstone’s growth was even more dramatic, jumping from 250 to 1,200.

In some ways, Cornerstone did look like Bill Hybels’s Willow Creek or Stanley’s North Point. They put on elaborate theatrical performances to draw in community members, created a professional-level kids’ program, and built an auditorium that could hold 1,800 people.

But in some ways, Cornerstone didn’t look like Willow Creek at all.

Reformed Theology

“We would go to a Willow Creek conference to learn about how to do ministry,” said Mark Arant, who came on staff with Salt around then. “But we’d go to Bethlehem to learn theology.”

By “Bethlehem,” he means the conference and resources put out by Bethlehem Baptist Church in Minneapolis, then led by longtime pastor John Piper.

The person influencing Cornerstone toward Bethlehem was Jeff Dodge. Jeff had come to Christ in college, when he asked a guy if he could borrow his ID and the guy gave him the gospel instead. Jeff came to Christ, stopped smoking pot, and started listening to R. C. Sproul and John MacArthur. He went to seminary, then he went to seminary again. Over the years, he’s collected an MDiv from The Master’s Seminary and a DMin and a PhD from Midwestern Baptist Theological Seminary.

In 1996, Troy asked him to head up The Salt Company. It was a good choice.

“When I first got there, they were saying things like, ‘We just tell people not to bring their Bibles because we don’t want the unbelievers to feel bad when they walk in and they’re the only ones without a Bible,’” Jeff said. “And I was like, ‘That is the stupidest thing I’ve ever heard. That ends now.’ But Troy was great. Troy was like, ‘Hey, whatever you want. We brought you in to do what you think is right.’ And I didn’t say that out of disdain. What I was watching, whatever they were doing, was incredible.”

Jeff looked at all those college kids, on fire for the Lord, and wanted to teach them theology.

“I’m like, ‘We need substance. We need biblical literacy,’” he said. “It was a great match because Troy would often push me to do things that I didn’t think I could do, because he was like that. He could motivate, he could fuel you with vision. I was more the get-anchored-in-the-Bible [guy]. . . . We got enough ESV Bibles to give to every single soul, so everybody would be reading their Bible.”

Jeff taught the Scriptures expositionally, both Thursday nights and, later, when he became a pastor at Cornerstone, on Sunday mornings. Then he designed something called Gospel 101.

“It’s a five-week course,” said Sophie Newberry, a senior in college this year.

“It lays out the definition of the gospel as the good news that God saves sinners through the birth, life, death, and resurrection of Jesus,” she said. “Each week it focuses on a different part of that definition. . . . I’ve taken Gospel 101 every semester of college so far and I’m constantly learning new things and being able to pull out different things from different verses or the definition itself.”

One of my favorite things about Gospel 101 is the homework.

“Each week it prompts survey questions,” Sophie said. “One of the survey questions for week one is ‘On a scale of 1 to 10, how would you rate humanity?’ Then we just go to random students on campus and ask that question. And then they’re like, ‘Yeah, like probably 5, 6. There’s good people, but there’s also bad people.’

“And then you flip the question to ‘How would you rate yourself on a scale of 1 to 10?’ And they can say, ‘I think I’m a 7. Like I’m pretty good.’ And then we have the opportunity to be like, ‘Can I tell you why I think I’m a 0?’

“Gospel 101 gives opportunities to fuel conversations like that, and in a way that we can phrase it like, ‘I’m taking this class and I have to do these survey questions. Can I ask you some?’ Because it’s less intimidating when it’s homework.”

By the time students are done with Gospel 101, they should have a clear grasp of the gospel, the beginnings of a theological framework, and experience having conversations about faith with non-Christians.

The Gospel 101 curriculum is so effective that Jeff wrote it into a book that’s used by every Salt Company today.

“And then Captains is a Monday morning meeting where we walk through Wayne Grudem’s Bible Doctrine, the abridged edition of Systematic Theology,” said Graham Spruill, who leads Salt at Iowa State today. “This week it’s on the Trinity. So those are kind of the different streams to impact the head. And then weekly, our student [leaders] are in discipleship groups, which is either with our staff or a community member, you know, a lay leader on the church side of things, to just care for the heart as they do the job.”

That close discipleship connection to church members is the direct fruit of Troy’s decision to move to a local church ministry. So is the clear on-ramp for college students in Salt to join Cornerstone.

It works like this: A student gets invited to Salt events, where he or she hears the gospel and hopefully accepts it, responds in community, and starts to be discipled by peers in small groups. The leaders are constantly inviting their small group to church—and not just “Want to come to church on Sunday?” but “I really want to see you at church on Sunday. Can I pick you up?” And then after a pattern is established, it’s “I’ll text you what time I’m going to grab you from your dorm.”

Cornerstone lead pastor Mark Vance said about 60 percent of the students who come to Salt on Thursday night also show up at church Sunday morning. Throughout the semester, all baptisms are done on Sunday mornings with the church, the students are invited to special equipping events at the church, and there’s special encouragement to come to church during Advent, Lent, and Easter.

To be a student leader in Salt, a young person must become a student member at Cornerstone. Mark said these leaders are expected to attend church on Sundays, serve in ministries, give financially, and go to members’ events. Their discipleship groups are led by church elders or core members.

Mark told me his goal isn’t a four-year college experience but planting seeds of godly growth that could one day result in these students becoming elders and pillars in their own local churches.

After nearly 40 years of this, this is what Iowa State looks like:

“I can’t walk into the MU, which is our Memorial Union, and not see people being approached and asking spiritual questions and having conversations,” Morgan said. “It’s impossible. I’ve been approached so many times by people who are like, ‘Do you believe in God?’ I’m like, ‘Yes, I do. I’m actually a leader at Salt. Thank you. Let’s have this conversation.’ Because they’re like, ‘I don’t want to bother you then.’ I’m like, ‘No, if you want to talk about God, I will talk about God. But come back when you’re done fishing, you know?’

This is fascinating to me, because the Iowa State that Morgan goes to isn’t the same place Brent and Tori attended. America’s shift away from religion has been especially pronounced among the younger generations and on university campuses.

That was already visible back in 2010, when the percentage of freshmen who’d attended a church service in the past year had dropped to 75 percent. Christian professors and students were starting to complain about religious discrimination. Over the next decade, a handful of campus ministries (including the Christian Legal Society, InterVarsity, Cru, and Young Life) were kicked off campus for requiring members to hold to Christian beliefs—specifically, that sex belongs inside marriage between one man and one woman.

One of the places that has shown some of the most blatant hostility to Christian groups is the University of Iowa, just two hours down the road from Iowa State.

University of Iowa

To understand the next part of the story, you need to know something about college rivalries. This is what happens when two schools are relatively close to one another and compete regularly, most noticeably in sports. Nearly every school has at least one main rival, and the emotions around them can be intense. Think Duke vs. UNC, Auburn vs. Alabama, or UCLA vs. USC.

Iowa State’s biggest rival is the University of Iowa in Iowa City. The state’s two biggest schools are two hours apart and play each other in just about every sport. Intensifying the rivalry is the fact that the state of Iowa has no major professional sports, so most of the state’s population end up picking one as their favorite team.

Unsurprisingly, the Salt alumni and their families cheered for Iowa State. One of Troy’s daughters, Trisha, grew up dreaming of playing basketball there. She was an excellent point guard in high school, so it wasn’t outside the realm of possibility.

But that’s not what happened.

“[She] didn’t get an offer at Iowa State because they had plenty of point guards,” Troy said. “But she got an offer to play at the University of Iowa, which is close, and she wanted to stay close. And so at that time, man, they were the enemy. This is our big rival.”

Troy and his family gritted their teeth and supported Trisha as she headed over to Iowa City.

“When she took that scholarship, we decided to go help her find a church,” he said. They visited a few places but couldn’t find anything that had both good theology and a love for young people.

So when Troy got back to Ames, he asked Mark Arant, who was leading The Salt Company then, if he’d plant a church and a college ministry in Iowa City.

This wasn’t an attractive opportunity. The folks at Cornerstone had just finished construction on a new space. Not only would Mark not get to enjoy it—and the momentum of The Salt Company—but he’d have to start from scratch at a school he’d been cheering against since he was a freshman in college.

Well, almost from scratch.

“Troy’s like, ‘Hey, just anyone on staff—ask them,’” Mark said. “So we went to our Salt staff. We sat in Jeff Dodge’s dining room and I announced to them, ‘I’m going to Iowa City. Who wants to go?’ And we went around, and all of them said, ‘Yeah, we’ll go.’”

“Well, you can’t all go,” Mark told them. “Let’s take some time to think about it.”

A few days later, Mark announced the new plant at The Salt Company and asked the students, “Who wants to go?”

“There were over 100 students that stood up and said, ‘Yeah, we want to go,’” he said.

Really? The Salt staff all wanted to go back to eating beans and rice in a new city? The Salt students—some of whom were seniors—wanted to transfer to a new school where they didn’t know anyone?

The next Sunday, Mark stood up at Cornerstone and asked the same thing. Brent and Tori were there, along with their high school senior. Luke had decided to enroll at Iowa State, and they were so thrilled they’d bought him Iowa State clothes for Christmas.

“So Tori and I are Iowa State graduates,” Brent said. “Tori has two sisters, and they’re both Iowa State graduates. They both met their husbands here—both Iowa State graduates. I have two sisters. They’re Iowa State grads. They both have husbands. They’re Iowa State. And so, you know, the University of Iowa is our rival.”

“We’re kind of pro–Iowa State,” Tori said.

“Yeah, we’re big Iowa State people,” Brent said. “We live in town, you know?”

“We raised our children to be Cyclones,” Tori said. “But Mark asks—”

“And out of the corner of my eye, I see somebody stand up,” Brent said. “And I look, and I say, ‘That’s my son.’”

“Not only did he stand, but he was sitting right next to me, and he stood like he was 85—you know, he pushed up on the chair very shakily,” Tori said. “He knew the weight of this. He was just shaky because he had chosen to do this really hard thing as an 18-year-old.”

What on earth? Why?

“He intimated something to the effect of ‘I know how important that was for you and Mom, and I just wanted the opportunity to try to do something like you were able to do that is impactful,’” Brent said.

‘All God’s Grace’

In the summer of 2010, about 50 Salt kids transferred from Iowa State to the University of Iowa. Of the seven Salt staff, six chose to move. One stayed behind, but only because somebody had to rebuild the staff to serve the 800 kids coming to the original Salt.

There’s strength in numbers, but still, there was no guarantee this second Salt Company was going to work.

“Iowa City—it’s a very liberal city,” Mark said. “It’s a different kind of university. They have the Writers’ Workshop. They have more of a liberal arts culture. Marilynne Robinson’s there, and it’s kind of a bastion for literature and the arts. It’s different. Someone well-intentioned, a pastor, sat me down and said, ‘This isn’t going to work there. It’s a different place. So if you’re planning on trying to do Cornerstone Church in Iowa City, it’s just not going to work.’”

That pastor was right about this: The campus was more liberal. The University of Iowa was the first state university in the country to recognize a gay student organization and to offer insurance benefits to employees’ domestic partners. By 2010, they had a Pride House, degrees in gender and sexuality, and a medical student club advocating for LGBT+ health care.

“When we got to Iowa, it was more common for students, as part of their college experience, to experiment with same-sex relationships or hookups to find out, Is that part of who I am?” Mark said.

So it surprised everyone when Veritas Church and the University of Iowa Salt Company took off. Students wanted to hear God’s Word. They wanted to confess sin. They wanted to learn theology. And community members—especially those older than 50—wanted to be in a church that focused on youth.

Within three years, about 600 people were coming to Veritas—400 of them part of the college ministry.

“I’ve always said that I think a trained monkey could lead Salt Company because we are standing under a particular waterfall of God’s grace that is truly amazing,” Mark said. “Anything that worked—it was obviously God. I think in the 2,000 years of church history, there’s never been a more spoiled church planter than me.

“It’s like a ball that’s put on a tee, and even if you miss the ball, you still hit the tee, and the ball still goes and you still get to first base. It was from the Lord and so now, how much more obvious is it that it was all God’s grace?”

Growth on a Gen Z Campus

Over the last 11 years, with help from the Southern Baptist Convention, the Salt Network has planted churches and started Salt Companies in around 30 places—including the University of Kansas, University of Wisconsin–Madison, Ohio State, Syracuse, Purdue, the University of Florida, the University of Oregon, and the University of Nevada, Las Vegas. By the end of 2024, the Salt Network served more than 12,000 college students in 16 states.

Some of these chapters are exploding—like in Florida, where 1,200 kids showed up for the Salt kickoff in August. Some are a little smaller, like at Syracuse, where Salt isn’t allowed to operate on campus and has to hold its meetings in other nearby locations. But all are growing, and in a university climate that’s more liberal every year.

From 1989 to 2017, basically from the time Troy launched the first Salt to when the expansion began, the percentage of university faculty identifying as politically liberal grew significantly, and the percentage of liberal administrators grew even more. By 2017, for every conservative faculty member, there were five liberals. For every conservative student-facing administrator, there were 12 liberal or very liberal administrators.

That’s not great news for Christians, because those who are politically liberal are statistically less likely to believe in God or call themselves evangelical Christians.

The lopsided number of liberals has also contributed to the growth of things like trigger words, safe spaces, rescinded speaking invitations or the firing of those who seem too controversial, and a lot of self-censoring from students and faculty alike.

What does this mean for Salt? How do Christians effectively engage a secular campus in 2025?

They jump right in.

“The first couple of weeks of school, they throw so many different events that it’s impossible to run into someone on campus who hasn’t heard of something that’s going on,” Sophie said. “The week before school is freshman move-in week on campus. As student leaders, we do an event called MTC, which is Mission Trip to Campus. During the day, we’re trying to meet students that are walking around and tell them about the events that we have going on.”

“They had a bunch of puppies on campus with lollipops one day,” said Sydney Hoggard, a senior at the University of Oregon.

“The environment that we have here is a sport heavy, very social environment,” said Austin Fisher, also a senior at Oregon. “We do Saturday morning football. We go out on the fields and play touch football. We have like 30 guys who come out. We’ll go hiking or we’ll have sports games, and we have intramural clubs and stuff like that.”

A lot of this might seem obvious—for decades, campus ministries have been pulling kids in through activities and relationships. But campus ministers tell me that Gen Z, hampered by cell phones and COVID-19, is struggling to connect.

At Iowa State, one student told Sophie that it was intimidating to be in the worship time with 1,000 other kids. Another told Graham Spruill that the church lobby was causing social anxiety.

“Would there be a day in which in the big gathering we’d need to plan some more acoustic sets, because it’s anxiety-inducing to be ripping five songs that are high energy?” Graham said. “I think we want to keep our pulse on that, given the anxious generation.”

The Anxious Generation

Let’s dig into that a little bit. We know that from 2010 to 2019, the percentage of undergraduates with a diagnosis of anxiety more than doubled, from 10 percent to nearly 25 percent. Increasingly, I’m hearing young people say things like, “Anxiety is part of my identity.”

“I’m not trying to put all of Gen Z in a box, but I think the core struggle is certainly anxiety,” said Conell Christiansen, a Salt ministry leader at Iowa State. “Part of the reason why people are anxious, why people are afraid, is centered around this identity question: Who am I? What do I believe? What do I feel?”

I hear what he’s saying—this generation is struggling to come of age without much help from moral codes, healthy cultural expectations, or strong community ties. Social media makes this struggle much worse.

“Most of us got it in middle school,” Sydney said. “It really creates this idea in your head that you have to have the perfect life. You have to put on a show. And all of that is just not real. It’s not real life, and you’ll never be perfect.”

You don’t have to look at anxiety from this angle for long before you can see the pride underneath it.

“I’ve just seen a transition [in my life] of learning to not need to control every aspect of my life and not being perfect,” Morgan said. “Those were the two key parts of my anxiety. Coming to fully believe the truth diminished so much of that anxiety, because it was like, I actually don’t have control of my life, and that’s OK. I can give that to God. And I can’t be perfect. So it’s like, he’s perfect for me. It’s OK. So that really helped with that anxiety.”

Morgan told me that anxiety can sometimes be the way a person relates to those around her.

“A lot of people are putting it on themselves,” she said. “They are literally finding reasons to become anxious and making themselves anxious because that’s what fitting in looks like for our generation. We had a negative, painful mindset that if something was bad for someone, it had to be worse for you. Like with sleep: We’d be like, ‘I only slept for five hours.’ ‘Well, I only slept for three and a half.’

“There was this mentality that we wanted to be in the lowest, the worst possible state. I don’t know why that was. I think for me it was like a cry out for ‘Please give me love and attention and care for me.’ But it’s like a whole generation of people who are wanting to be in the worst possible shape.”

At first glance, this might look like humility. But for Gen Z, the social power structure is flipped.

“The victims or the people who are oppressed have more of a voice,” Morgan said. “It’s like, ‘Everyone else doesn’t get an opinion because I’ve been oppressed. So I’m the one who should be talking.’

“I think that’s spread really far, really fast. And I think a lot of people are like, ‘I want to be with that oppressed group because then I can share. I’m right. I’ve been hurt so I get to speak on this.’ It’s like a superiority thing too: I want to be the worst but I want to use that because I want to show you that I’m better because I’m lower. It’s a really weird inverted scheme.”

For Morgan, coming to Christ and walking out her faith with girls in her connection group, or C-Group, significantly decreased her anxiety. I heard that from others too. Students who believe in Jesus can stop trying so hard, stop glorifying brokenness. They can rest in Jesus’s perfection, his sovereignty, his care for them. They can serve instead of asking to be served.

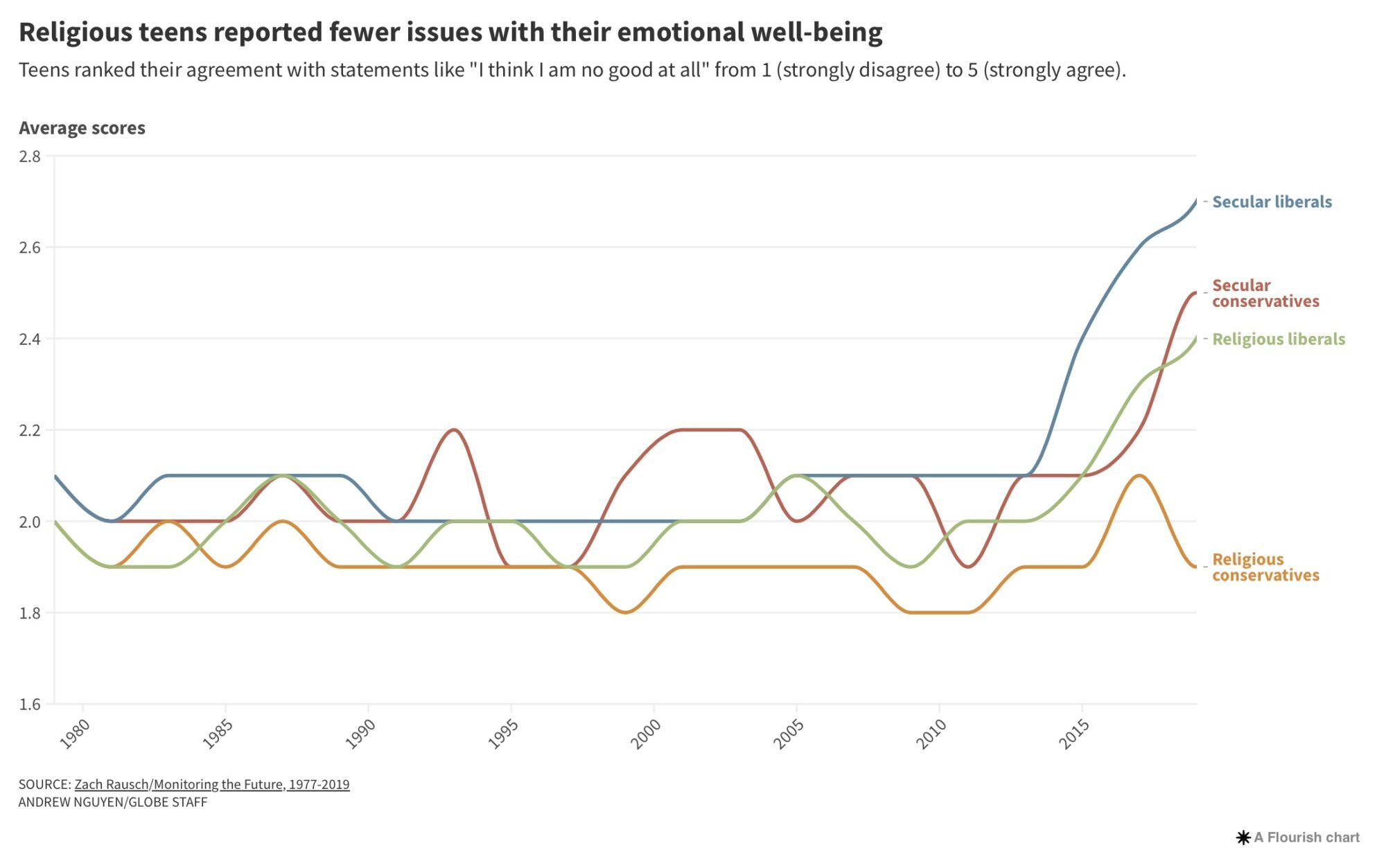

When Jonathan Haidt wrote The Anxious Generation, there was one chart he left out. This summer, his research assistant released it in an article called “Why Are Religious Teens Happier than Their Secular Peers?”

Here’s what he wrote: “Teens without a religious affiliation across the political spectrum started reporting that they felt lonely, worthless, anxious, and depressed at much higher rates starting in the early 2010s. However, religious teens, especially those who report being more conservative, did not.”

You can see it in his chart—kids who are religious and conservative report significantly better mental health than their peers who are secular, liberal, or both.

“The secret,” wrote the researcher, “is likely not any particular belief system but the way organized religion and shared beliefs bind communities together.”

Hmm. That’s not exactly what I’m hearing. Community is really important, but it doesn’t change lives the way the gospel does.

That’s why one of the first things students hear in their Salt connection groups isn’t a comfortable speech about Jesus’s care for the anxious and depressed. The first big idea, introduced through testimonies, couldn’t be less comfortable or more challenging and unpopular.

It’s sin.

Sin

“When I got to my first couple of C-Groups, with only a couple of people, it got really personal really quick,” Morgan said. “We had the chance to share what our lives were like and to be met with such love and not judgment from my leaders. Some things are really shameful for me and I’m carrying a lot of brokenness, but they weren’t shaming me. They just wanted to get to know it even deeper and to know how to better love me through that.”

At the beginning of each year, C-Group leaders share their testimonies, including some of their past sin that Jesus has taken away. This honesty and vulnerability comes from Troy’s DNA, but the idea of sin isn’t nearly as socially acceptable as it was back when Troy was leading the discussions.

“The concept of ‘sin’ is rarely expressed in today’s popular culture,” author Hilary Brand wrote after doing research in 2016. “When the word does appear, it is frequently in ironic quotation marks and often used in terms of ‘naughty but nice,’ minor misdemeanours, something disapproved of, an outmoded Catholic shame culture, Islamic oppression or fundamentalist extremism. Rarely is it used in the way the Church understands it.”

The word “sin” has grown so unpopular that in 2007, the Oxford Junior Dictionary removed it, arguing it was no longer “language children will commonly come across at home and at school.”

In a hypersensitive college culture, you’d think leading with the idea of sin might not be the best idea.

But to a lot of students, talking about sin feels like being authentic.

“I feel like Salt Company does a great job about being very authentic and real,” Sydney said. “And that’s something that’s difficult to find, especially in the Pacific Northwest, because people don’t really grow up Christian. And so a lot of churches will push the love part of the gospel—and I think that’s super important. But Salt Company also brings in the truth part. And so that was something that I was really looking for—people to not call me out but call me up and out of sin.”

Sydney said the sins she sees students struggling with the most are the misuse of alcohol and sex.

It makes sense to me that kids—especially Christian kids—would identify those as sin. But I know college students these days aren’t as likely to grow up in a Christian household. In the public schools, sexual experimentation and pornography use are often seen as normal and healthy. So what do those kids think about the confession of these as sins?

“There definitely are some things with some of the guys where we’re confessing and they maybe don’t agree that it’s a bad thing,” said Austin, who’s studying financial management. “Like with porn or with drinking, they’re like, ‘I went out and drank, but I didn’t black out or I didn’t throw up on other people. So I’m healthy. I’m not gonna die from it. If I do it more often and heavily maybe, but I’m not at that stage right now.’

“It’s kind of like there’s levels to this kind of thing. There’s definitely other things where they may not understand why we’re confessing it, but they kind of get the gist of how it affects the rest of the group.”

As you can imagine, confessing sins of pride or discontentment or laziness can be even more confusing.

“I definitely had parts of my life that I compartmentalized and didn’t want to fully give to the Lord, and a lot of that had to do with the overachiever mindset that I have,” Sydney said. “I just had my goals and I had my plans and I didn’t want to allow God to move within that.”

Sydney confessed that to her C-Group. I asked what the unbelieving girls thought of that.

“It’s definitely different,” she said. “But a lot of girls that come to C-Group are very open to hearing everything. And it definitely allows for a lot of deeper conversations. I’ll have girls text me after and be like, ‘Hey, I really want to learn more about what you said. That was interesting. Even though I don’t think that’s a sin, I would like to hear more about how you do think it is sin.’ And that just opens so many doors for really great gospel opportunities and conversations.”

It’s also helpful for sanctification.

“I’ve been a Christian my whole life, I had faith my whole life, I’ve been committed to Christ my whole life, but it hasn’t always looked like it,” Austin said. “The past six months since joining a C-Group and getting plugged in with those guys and walking with brothers in faith, I’ve realized there’s so much that I thought was normal and may be normal to secular communities but in faith and church is like, ‘Hey, that’s something you got to cut out.’ It may not be a huge sin like porn or like drinking or partying but it’s the thoughts I have. I’m not in control of them, but once they pop into my head I don’t have to dwell on them. I can push them to the side. Or the way I talk, whether it’s swearing or gossip or whatever.

“I have been reignited with this passion and with this fire to be like, OK, I want 100 percent of my life and every aspect of my life—not just what I project to other people, not this front that I have—I want everything in the background to be completely devoted to Christ and reading his Word and applying it to my life.”

At Salt, finding gospel clarity on what’s true and not, what’s right or wrong, extends beyond personal confession.

“There was just something different about being around the people that were in Salt,” Haywood said. “C-Groups were a place where we were talking about things. I remember one C-Group we started talking about pronouns for people, especially, like, in the LGBTQ community and then biblically how we should be as Christians. That was never a topic I would ever delve into. I’m like, Whoa, really? This is something you guys talk about? Aren’t you supposed to say, ‘Jesus loves us and let’s go home’? Like, what?

“These guys are actually ready to stand and talk about things that are uncommon for people to talk about, especially our age, because a lot of our generation just goes with the grain, goes with the flow, isn’t really about sticking out or being canceled. And it really showed me, Man, there’s a level of you that can stand on what you believe, even if it’s unpopular. That really just drew me—that light. And just like, Man, this is what I’ve needed my entire life. It brings me so much joy. It’s so fulfilling.”

Morgan had the same experience.

“I remember going to the conference and hearing Mark Vance talk about gender and sexuality, which was a really hard subject for me, because I was comfortable not standing out,” she said. “I was like, Oh, I’m a nice person, so the nice people don’t say controversial things. And both of my siblings would say that they’re LGBTQ members. So I was like, I don’t want to go against what my family believes.

“But I felt like, No, you need to stay and listen to Mark talk about this. And being in that room exposed me to, Oh, wow. God has a beautiful plan and purpose, and his Word is good, and it’s not bad. And it started a journey of, Oh, I really want to know what God’s plan is and what his design is, because it’s not a bad thing. And it might be hard for some people to talk about, but there’s blessings in that.”

Another huge advantage of talking clearly and openly about countercultural issues is that now C-Group members can help each other out. Every day, the student leaders Conell is discipling text him how many days it’s been since they looked at pornography. At Oregon, Austin and his roommates skip sex scenes in movies and encourage each other to stop lustful thoughts as soon as they pop into their heads.

At Iowa State, having Christian friends helped Sophie to be bolder in class.

“Last semester, I was taking a happiness class,” she said. “It was the science behind happiness and well-being. We talked a lot about the science backing up why moving your body makes you feel good and why meditation and things like that are like good for your mind. We talked about instant gratification and how in the moment that’s great, but then 10 minutes later, am I still riding that high or has that kind of fanned out?

“That was something I wanted to grab hold of and be like, ‘Yeah, there’s so many things that we try and grab hold of, that we think are going to satisfy us long-term, but really it’s instant gratification. Sin feels good in the moment. And if I were to go out to a party or do something crazy, sure, that would be fun in the moment, but I’m going to leave that feeling so just lost and confused and lonely.’

“And I slipped in, ‘Jesus is the only thing that’s going to satisfy you eternally.’ I had one of my best friends in that class. And I was like, ‘Hey, if I speak up, are you going to go after me so that you can reiterate everything I’m saying?’ She’s like, ‘Yeah, I got you.’ So that was helpful. She was like, ‘Yeah, and I second all of that. Here’s everything that she didn’t say that I’m going to add on to.’

I asked Sophie what her professor thought about that.

“The professor was like, ‘That’s great that that’s what you believe,’” she said. “Professors here, I’m noticing, are really good at giving the ‘That’s your truth, and I want you to be able to express that, and that’s beautiful that you believe that, but you don’t have to force that on anyone else. And we’re not going to unpack that at all. I’m not going to open that up for discussion.’”

I’m curious about this, because it’s dawning on me that the generation of Christians who deconstructed their faith are probably Sophie’s professors.

Mike Graham, who cowrote The Great Dechurching, told me that, sure enough, the elder millennials have largely stayed in church while the Gen Xers and the younger boomers have gone.

“Dechurching in America will be a temporary phenomenon,” he said. “Like COVID-19 pandemic spikes, the spike eventually has to come down because there aren’t enough people who grew up in church to keep the spike growing. Hence, the thing that follows a spike in dechurching is a spike in the unchurched a generation later. In other words, dechurched parents raise unchurched kids.”

That makes sense, and it’s exactly what campus ministry leaders are telling me.

“Generationally, most of our college students in Salt Company are going to be first-generation Christians,” Mark Vance said. “We have a fraction that come from fervent believing homes. Let’s call it a quarter. Then we’re going to have another quarter that come from nominal Christian homes, another quarter that came from ‘I’ve heard of Christ,’ another quarter with nothing. But the vast majority of them don’t know Adam from Moses at all.”

Are those unchurched kids of dechurched parents hostile to Christianity?

“There certainly is opposition, but I think a lot of times for students, it’s just not on the radar, or in their worldview even,” said Joanna Gramer, the associate director of Salt in Syracuse, New York.

“I personally haven’t had any hostile interactions,” Austin said. “I would say the majority of them are kind of just indifferent. When I say I’m going to church or a church group or a ministry or a Christian group, people are like, ‘OK, cool.’ Like ‘good for you’ kind of thing. I would say neutral indifference or extreme interest are kind of the two options.”

“I think a big phrase in my generation is the phrase ‘Live your truth,’” Sydney said. “And it kind of enables people to be like, ‘OK, that’s what your truth is, but my truth is different.’”

The “my truth, your truth” language can be frustrating when Salt students try to explain the one truth. But it also seems like the buffer of “my truth, your truth” allows a little bit of space for conversation.

“This generation—they want to know what’s true and they want to figure out what they believe,” said Joanna. She told me about one of them, a girl who started coming to Salt two years ago.

“She was a student athlete and had been at Syracuse for five years,” Joanna said. “She was doing grad school and had a background in Catholicism, and yet was at a place that year where she was trying to figure out what Jesus, what religion, was—if there was more than what she had grown up experiencing and more to the college life.

“She began coming and hearing the gospel and, early that fall, understood and believed. She went from partying and sleeping with her boyfriend and fill in the blank to leading a group and witnessing to her friends. I mean, the incredible work that God did. Her life is now committed to him.”

“I have just seen so many transformations that I didn’t even think were possible,” Sydney said. “Seeing that God can work through any situation and through anybody has been so incredible. In particular, up here, there’s a lot of witchcraft, a lot of people practicing crystals, astrology, tarot cards, and I’ve seen so many girls that were just so deep into that and came to Salt Company like once or twice and decided that Jesus was the life for them. And just seeing that transformation has been so encouraging for me and has really encouraged me to pursue more ministry opportunities within Salt Company.”

I heard that over and over again. Salt students are being changed—and watching other people be changed—by the gospel.

“I want to say there were 13 or 14 students who got baptized last year,” Austin said. “There were four guys who I would meet with one-on-one outside of the Salt Company, to chat about life. . . . It’s been incredible from the first week of spring, meeting these guys, and seeing how their lives were with the partying and drinking and all that to now, I would say three months later, seeing how drastically their lives changed just by being in a community of men who held them accountable and were pushing them . . . going from people who weren’t baptized and didn’t really know much about faith, or who might have had a small background, but weren’t super interested, to being baptized, completely committing their lives to Christ, being small group leaders—just like a complete 180 of their faith. It has been absolutely incredible. And I know that’s a story for a lot more people.”

Revival

A few months ago, I asked college ministry leaders if they were seeing a revival on college campuses.

“I’m always hesitant to try to describe an entire generation at once,” said Greg Jao, who has worked at InterVarsity for nearly 30 years. “But at least in InterVarsity Christian Fellowship, what we’re seeing is a very deep hunger and spiritual expectation that feels different from the activism and . . . the let’s-change-the-world energy we saw in the millennials.”

“We’re hearing reports on campus of large groups of students seeking to be baptized as a sign of their surrender to Jesus as Savior and Lord,” he said. “We saw it at Auburn. There’s been a lot of talk about Ohio State recently. We’re hearing more and more stories of physical healings. And what’s been striking as I’ve been talking to conference directors is not just that more people are coming, which is lovely, but there’s a deep hunger for worship and prayer that seems different.”

Cru is seeing the same thing.

“I’m certain this isn’t happening on literally every campus across country, but from my run-ins with students on the East Coast, I’m seeing a real groundswell of excitement for the gospel—to the point that others I know who lead campus ministries are talking about it and it’s getting them super hyped up,” he said.

Numbers are increasing, “but that’s not the only measurable aspect,” he said. “People are coming to Christ, discipleship is being taken very seriously, and commitments are being made to short-term and long-term missions. I don’t know if this is happening everywhere. Frankly, I’ve asked the same question that a lot of people have asked: Is there really revival happening on campuses?”

“I’m hesitant to make pronouncements, but it does seem across the board that good things are happening—an acceleration,” said Campus Outreach executive director Olan Stubbs. “I’m seeing more—and now I’m thinking more of our staff, but it trickles down to students. More prayer, more fasting, more of a hunger for an out-of-the-ordinary outpouring of the Holy Spirit. I’m cautiously optimistic. I’m hopeful.”

So am I. Because at the Cross Conference this past January, 15,000 young people maxed out the space. Organizer Matt Schmucker told me that by God’s grace he’s seen more than 30 percent growth year over year. Next year, Cross Con will hold two back-to-back conferences to allow for more room.

At Campus Outreach’s New Year’s conferences in Texas and Tennessee, about 1,300 kids attended—the most they’ve ever had. Nearly 50 of them reported conversions.

I don’t know if we’re looking at the beginning of a full-scale revival. But here’s what I do know:

After Austin graduates from the University of Oregon, he plans to take a financial planning job in Eugene so he can continue his involvement with Generations, his Salt Company church.

When Morgan finishes up at Iowa State, she’ll choose between a couple of ministry opportunities, either in the States or overseas.

When Sydney gets her degree from Oregon, she’s headed to graduate school. She narrowed her choices to two—one in Knoxville and one in Denton—because that’s where Salt is planting new ministries, and she wants to help.

By the time this article comes out, Sophie will have graduated and moved to Las Vegas to look for a job and to help with the brand-new Salt church plant there.

These students are doing what Troy and Jeff and Mark did, what Brent and Tori did, what Luke did when he stood up and said he’d transfer to the University of Iowa. They’re choosing a harder life—shaping their future around the spread of the gospel and the planting of churches. They’re choosing to eat rice and beans, to give up their evenings and weekends and maybe their year-end bonuses, to share the gospel of Jesus Christ with their generation.

“The people around me are so ready to get after it,” Sophie said. “They’re like, ‘We literally have the best news ever. I’m going to go tell everyone I know about it.’”

For God So Loved Gen Z

“I see God working in Salt Company, where he’s really stirring up young people in this generation that I think a lot of the world has given up on,” Haywood said. “As the world gets more evil and darker, that means this light—it has to shine brighter.”

Yes. As the culture darkens, especially on university campuses, the light of Jesus is shining brighter. As the promises of sin prove themselves false, the image-bearers of God in the next generation are looking for something better.

What they’re finding is an identity more beautiful than any brand they could imagine for themselves, a salvation more holy and gentle than any virtue signaling, a security stronger than their anxiety. They’re finding a community knit tighter than their blood relatives, a purpose big enough to shape their lives around, a joy and relief so big they can’t keep it to themselves.

For God so loved this lonely, anxious, addicted, upside-down generation that he gave his only Son.

“The Most Practical and Engaging Book on Christian Living Apart from the Bible”

“If you’re going to read just one book on Christian living and how the gospel can be applied in your life, let this be your book.”—Elisa dos Santos, Amazon reviewer.

“If you’re going to read just one book on Christian living and how the gospel can be applied in your life, let this be your book.”—Elisa dos Santos, Amazon reviewer.

In this book, seasoned church planter Jeff Vanderstelt argues that you need to become “gospel fluent”—to think about your life through the truth of the gospel and rehearse it to yourself and others.

We’re delighted to offer the Gospel Fluency: Speaking the Truths of Jesus into the Everyday Stuff of Life ebook (Crossway) to you for FREE today. Click this link to get instant access to a resource that will help you apply the gospel more confidently to every area of your life.