Like most everything in America now, having babies is apparently a partisan decision, and it’s now become coded right. College admissions counselors eye the upcoming “demographic cliff” with alacrity. We all should be worried that in the US, the birth rate has dropped to historic lows since the country began tracking about 100 years ago. (In 2023, the birth rate dropped 3 percent from the previous year to 1.62 children per woman.) At the same time that men and women are more likely to forego parenting, motherhood particularly in the digital age has taken on a consumeristic edge.

Life as good and worthy per se is no longer key to our cultural thinking. Instead, children are signposts of one’s politics or used quite literally as accessories to lifestyle brands. In The Influencer Industry, Emily Hund explores the growth of the influencer industry (which Goldman Sachs estimates will grow from its current valued worth of $250 billion to $500 billion by 2027), particularly related to curated authenticity. Whether influencers sell goods via affiliate marketing, partner with brands, or simply monetize their feeds with advertising, everything is for sale.

While traditional societies may have regional and multigenerational safety nets, much of the Western world has turned to the internet in the past few decades for support. Back in 2002, when the internet felt like a free exchange of ideas and life stories, the mommy blogger was born out of a desire for community and potty-training advice. Over the years, what a mother went looking for online changed. As one former mommy blogger terms it, the writing of “gritty personal essays morphed into attractively staged, aspirational content.”

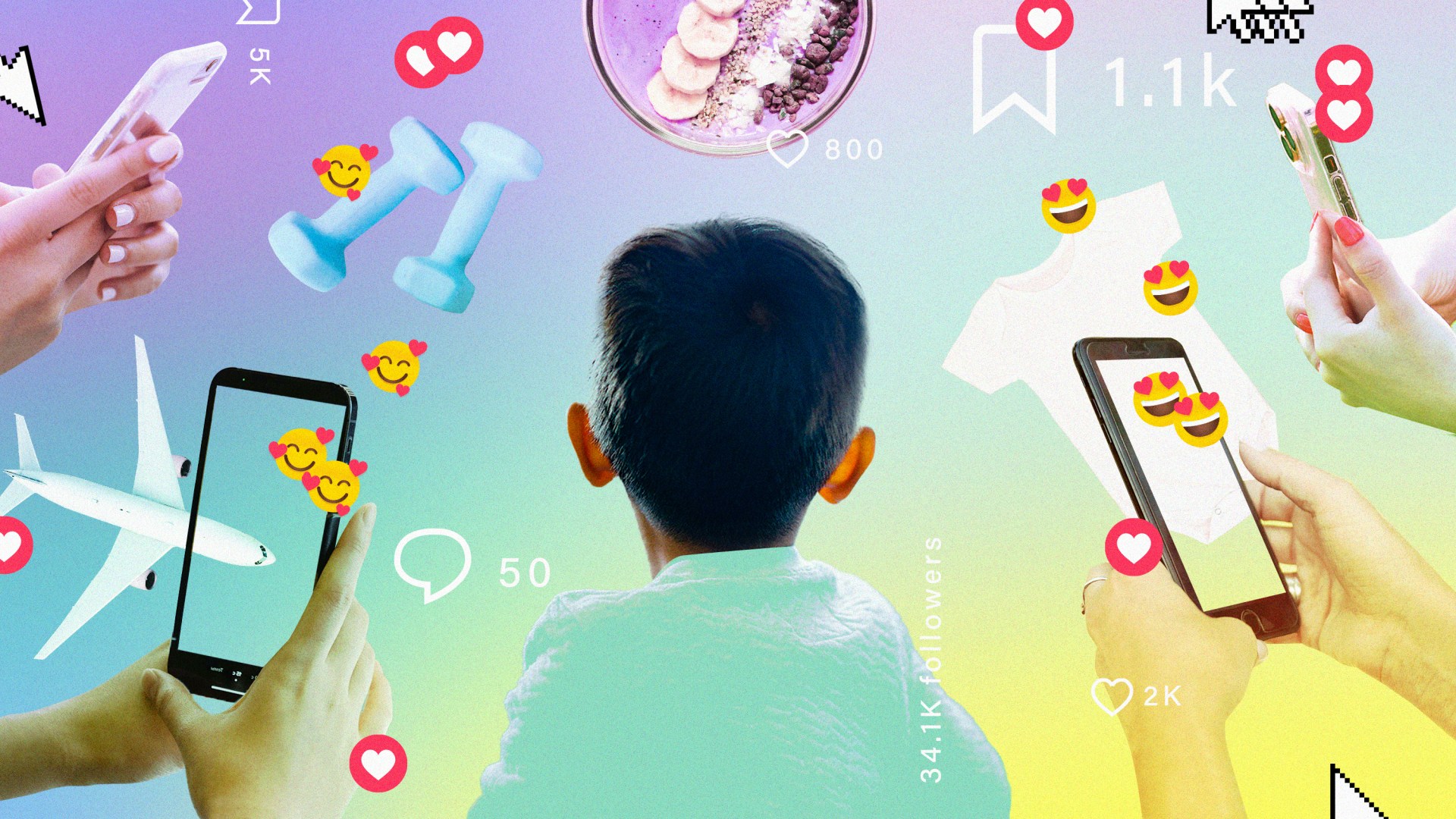

Today, mommy bloggers have been replaced with TikTok #TradWives who emphasize a stylized back-to-the-land aesthetic while carefully leaving out the manure or toddler meltdowns. Motherhood has become performative, and it’s harming real mothers, children, and families. These trad (traditional) wives sell us the allure of rootedness and of beautiful children parading like ducklings—without revealing any of their costs. They buy, sell, like, and share things that virtue builds slowly over time. Motherhood has become an industry.

“When monetizing one’s daily life is a growth industry,” Emily Hund asks, “where does it end?” Therein lies the rub. With phones in our hands, scrolling through reels with algorithms that increasingly serve us more of the same, we can easily become immersed in someone else’s life (or, at least, what they choose to disclose). As our attention equals monetary gain for someone or some platform, we must ask: What is the value of our attention? And when our attention is fixed on idealized squares of performed domesticity, who actually profits?

After all, authenticity is what makes one influencer more “valuable” than another. A little over a decade ago, a Nielsen study found that more than 90 percent of consumers would trust product recommendations from someone they knew (rather than a faceless brand). As the influencer industry has grown, authenticity and personality are no longer about connection but have become increasingly focused on metrics. “Only once influence could be measured could it be shaped into a good and assigned monetary value—and monetization was the goal,” writes Hund. What happens when we turn ourselves into brands? Or worse, turn our children into brands? What happens when we monetize motherhood?

Although many influencers are now removing their children from social media photos to restore a sense of privacy, the effect of monetizing parenthood is withering. Although not speaking about influencing specifically, writer Anne Lamott wisely observes that when we raise children “as adjuncts, like rooms added on in a remodel,” our children’s achievements become the parents’ “reflected glory, necessary for these parents’ self-esteem, and sometimes for the family’s survival.”

When we monetize children or look to their achievements to make sense of our own lives, we cut them—and ourselves—off from the gospel. If the influencer model, which works by teaching us to see ourselves and our children as moneymakers or influence bearers, tells us that we are only as valuable as the number of likes, follows, comments, or subscribers, what is the counternarrative for those who follow the Christian story?

Scripture repeatedly reminds us that God moves toward the failures, the murderers, the adulterers, and those without economic advantage, like the widows, the barren, and the sojourner. This is not to say wealth is bad: David and Solomon had great wealth and power, a circle of women supported Jesus’ ministry (Luke 8:1–3), and Phoebe supported the work of the apostle Paul (Rom. 16:1–2). The key is that no matter their amount, all these resources—whether monetary capital or social capital—were given in service to God and his kingdom.

While few of us are influencers, we’re all guilty of viewing what we do with our bodies—whether our fertility or our social media habits—as if we were our own. But we are not our own; we have been bought at a price (1 Cor. 6:20). If we’re parents, we’re likely guilty of wedding ourselves so tightly to the successes and failures of our children that we forget that children are not math equations where a particular input results in a specific output.

Children are people who need Jesus. Children of every age need to see the gospel enacted and lived out by their parents (and their faith communities), not through perfection but through obedience, failure, repentance, and grace.

Parenting by its very nature can’t be measured by algorithmic metrics or financial success, which are built into an influencer economy. To do so would be to say that the end goal of parenting depends on our own human action to influence or manipulate algorithms and spending habits.

But the good news of Jesus for mothers and fathers who are weary of trying to be perfect parents is this: Parenting is not about you. While your actions and the fruit of your life will impact your children, it is not clear how your children will turn out. Christian parenting is about continually pointing to Jesus as the author and perfecter of our faith, clinging to the reminder that he who began a good work in us and our children will complete it.

One of my favorite passages in Scripture that shows the emotional life of Christ is about how he longed to comfort and shelter Jerusalem. As a mother to four, I know the pull to shelter and protect while also needing to let go. Near the end of the Book of Luke, as Jesus heads toward his death, he compares himself to a mother hen: “How often I have longed to gather your children together, as a hen gathers her chicks under her wings” (Luke 13:34). Yet Jerusalem rebels. Pilate and the religious leaders conspire to kill Jesus. They are successful.

But the good news of the gospel is that this is not the end of the story. Just a few verses before Jesus’ response, some Pharisees tell Jesus to save himself: “Leave this place and go somewhere else. Herod wants to kill you” (v. 31). Rather than protecting himself or looking to worldly metrics that would shield him from suffering, Jesus responds by both acknowledging the truth of Jerusalem’s rebellion (v. 34) and reiterating that his response to rebellion is to gather his people under his wings and shelter them.

When Jesus uses the language of mothering, it is not to see people as expendable based on what they can do for him. Neither is it to accept rebellion against what he says is good, true, and beautiful. The response of Jesus is not to self-protect, run away, sugarcoat, or cut off. Rather, in Jerusalem’s failure and ours, Jesus always moves toward us with both truth and grace. That is good news for all parents.

Ashley Hales is editorial director for print at Christianity Today.