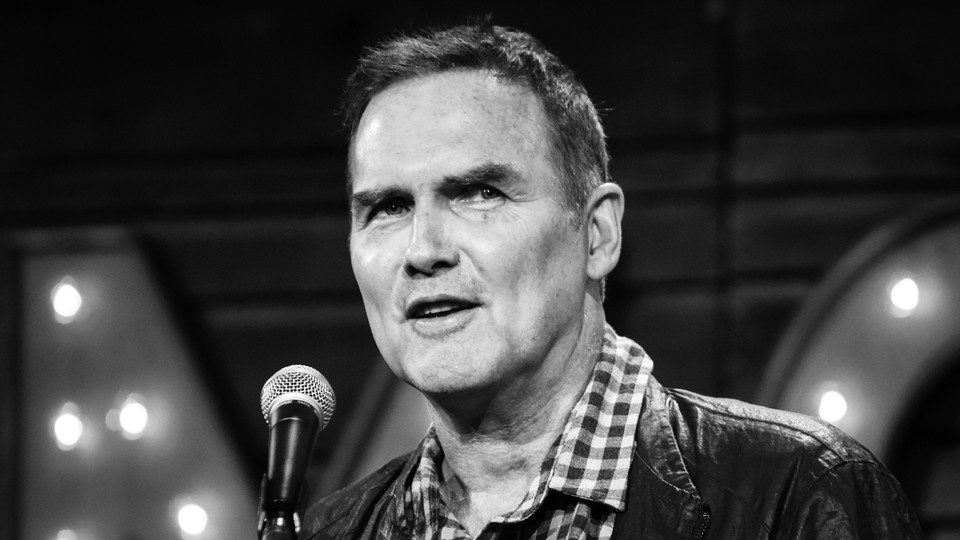

Norm Macdonald Wanted Laughter, Not Applause

The late comic’s best work exemplified his resistance to cheap, easy material, but also his utter unpretentiousness.

Norm Macdonald, the brilliant and lacerating stand-up comedian who died yesterday of cancer, once told one of the best jokes about the disease that I’ve ever heard. “In the old days, they’d go, ‘Hey, that old man died.’ Now they go, ‘Hey, he lost his battle.’ That’s no way to end your life!” he said. “I’m pretty sure if you die, the cancer also dies at exactly the same time. So that, to me, is not a loss; that’s a draw.” True to form, many news stories yesterday referred to Macdonald’s “battle” with the disease over the past nine years. But none mentioned that he fought it to a draw.

Macdonald was the purest kind of stand-up, someone who could sidle up to an issue as dark as cancer and talk about it with disarming frankness and goofy glee. He didn’t tell jokes to shock people or to deliver a polemic, but that didn’t mean he couldn’t be thought-provoking. He could create finely tuned routines that’d knock the house down, but he took just as much delight in eliciting roars of laughter from fellow comics by reading corny one-liners from an old joke book, to the bafflement of the audience at large.

Audiences might have known him best for his acerbic stint on Saturday Night Live from 1993 to 1998, where he hosted “Weekend Update” for three years before being controversially removed from the post. He starred in movies such as Dirty Work and Screwed, which flopped on release but quickly gained cult followings; headlined a network sitcom for three seasons; and launched short-lived talk shows on Comedy Central and Netflix. But above all, Norm Macdonald was someone whose comedy you could spend an entire night plumbing on YouTube—his late-night appearances, in which he’d set up rambling bits to baffle and beguile the hosts; his non sequitur stand-up riffs; his penchant for making celebrities laugh and gasp in shock in equal measure.

The Macdonald clip I—like so many others—watched over and over again was an early piece of online comedy virality: his segment on Comedy Central’s 2008 roast of Bob Saget. The roasts had become best known for the shocking lines comedians would lob at one another in one-upmanship; Macdonald decided to take the opposite tack, reading inoffensive gags from an old-fashioned joke book in a halting monotone. It exemplified his resistance to cheap, easy material, but also his utter unpretentiousness: He was thrilled to tell the worst jokes in the world and find new laughs in them. The act bombed with the live audience, but Macdonald’s fellow comics on the dais were cracking up as it became clear that he would stay with the shtick for the whole set.

Beyond the absurdity of the tame jokes (“Bob has a beautiful face, like a flower. Yeah, a cauliflower!”), Macdonald sells the entire thing with glee, struggling to hold back giggles as Saget writhes in hysterics. He was not a comic who shied away from shocking material—his hosting job at the ESPYs featured an O. J. Simpson joke that sent surprised laughs and angry murmurs through the crowd, and he was notorious for his knives-out approach on “Weekend Update.” But he could take almost any material and shape it into something hilarious, a gift that some of the finest stand-ups alive, especially those who rely on more personal storytelling, don’t possess.

His love of pure joke-telling, where craft and timing are far more important than any bearing on reality, is captured in the hours of material from his online show Norm Macdonald Live, during which he would catch guests off guard by having them read offensive lines off printed cards. As a “comedian’s comedian,” he landed in hot water after giving an interview in which he sympathized with comics accused of harassment and racism, such as Louis C.K. and Roseanne Barr. (He later walked those comments back.) In that interview, he also offered a surprisingly protective view of traditional stand-up, dismissing other idiosyncratic approaches to the form, which surprised me, given his talent for innovation as a stand-up. But even though Macdonald excelled at challenging expectations and sometimes seemed to revel in the silence following a failed joke, his philosophy was firmly rooted in the magic power that skilled comedians have, to get a rise out of the toughest audience.

He hated comedy that pandered to a like-minded crowd, once saying in an interview that stand-ups should hunt for laughter, not applause. “There’s a difference between a clap and a laugh. A laugh is involuntary, but the crowd is in complete control when they’re clapping. They’re saying, ‘We agree with what you’re saying; proceed!’” he said. “But when they’re laughing, they’re genuinely surprised. And when they’re not laughing, they’re really surprised. And sometimes I think, in my little head, that that’s the best comedy of all.”